Serial Killer Addresses 2014

It is November, and 5 a.m. Feels like winter. As he has on many mornings these past four months of 2011, Brogan Rafferty, age 16, wakes up early to help his friend and mentor, Rich Beasley, on an errand of Rich’s design.

Brogan doesn’t need to pick up Rich until 6, but unlike your typical teenager, Brogan likes to get up early and drink coffee in the morning so he has some time to himself before he leaves the house. Today they are going to pick up a man named Timothy Kern, age 47, who will be waiting for them in a strip-mall parking lot with all his earthly possessions. Like the three men who preceded him on this grim adventure, Tim answered an ad on Craigslist that said: We need someone to watch our farm down in southern Ohio. Live for free in a double-wide trailer, nothing in the way of duties except to take in the peacefulness of the countryside and remark on the changing of the seasons and make sure no one steals any farm equipment or perpetrates any mischief. The pay is $300 a week.Brogan pulls up in front of Rich’s with plenty of time and throws his Buick into park.

Rich comes lumbering across the front lawn, expelling steamy breath into the dark Akron morning, and deposits himself into the front seat. Brogan says nothing, as is his habit. Brogan is a junior of middling academic record at Stow-Munroe Falls High School, remarkable to his peers and teachers mostly for being such a giant of a human being. Six feet five inches, close to 230 pounds, and not finished growing yet. He’s a laconic character, polite but suspicious of authority, prematurely world-weary with an easily inflamed sense of injustice and an almost pathological ability to keep his own counsel. The agenda today can’t be a big mystery to Brogan.

The unauthorized address turned out to be the residence of his girlfriend, who had. July 2014); Fox News, “Police Say Accused California Serial Killers Wore.

After all, he was the one who dug the hole yesterday out at a plot of neglected suburban scrubland near the old Rolling Acres Mall—about yay wide and yay deep and big enough for an adult male body. Rich, not being partial to manual labor, had watched. As they pull out onto the road, Brogan wills himself not to think about what he and Rich will be doing this morning.Richard Beasley: age 52, former convict, motorcycle enthusiast, professed man of God, known on the Akron street as Chaplain Rich.

He’d started taking Brogan to church when Brogan was just 9 years old and already almost comically large and serious and quiet. Since then Rich has become probably Brogan’s best friend, his uncle-dad, his guide to the Gospels of the Bible and the affairs of the teenage heart, to the mysteries of Akron and the even deeper mysteries of Brogan’s own parents. Brogan calls him his counselor. It’s like Rich’s Craigslist ad was designed for a certain kind of person: male, white, unattached, aging, no longer fostering unreasonable ambitions or fueled by fantasies about what he might turn out to be someday, someone on the downward slope of life for whom things maybe haven’t gone exactly as planned. It is sort of a retirement plan for the obsolete white man. In the industrial northeast of Ohio at the far side of the Great Recession, there is no shortage of these people. Rich has actually been interviewing subjects he carefully selects from the hundreds of men who reply to the ads.

He’s been showing up at the food court of the Chapel Hill mall with an official-looking application form, affecting the air of an affable blue-collar-type landowner who just wants to find someone friendly to camp out on his spread while he’s up in Akron conducting the business of his normal life. Rich ascertains certain things from these gentlemen: Do you have a wife or kids or people you need to keep in close touch with?

This farm, it doesn’t have cell coverage; are you a fellow who can live in peaceful isolation? And what type of vehicle do you have, and would you be bringing that down with you when you came, and oh, there’s a laptop computer? Bring it all with you, and my nephew and I will drive you on down to Caldwell.Rich tells Brogan to get off the highway at an exit in the town of Canton. He says that Tim Kern is waiting in his car not too far from there.

Brogan is quiet, as always. People tend to make assumptions about you when you are huge and so quiet you could be mistaken for mute. But Brogan is also observant. Rich smells this morning of bar soap and, beneath that, something fetid. Brogan notices he’s wearing the same clothes as yesterday, and he wonders whether these are now the only clothes Rich has.

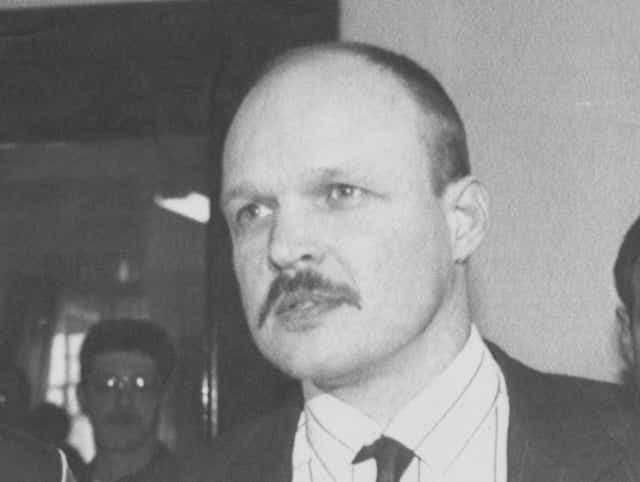

Rich has always been a rumpled character, a corpulent man in denim and leather and boots, with long white hair he wears in a balding grandmother’s braid. But one of Rich’s life principles is to maintain a bright hygienic line between him and the street people he ministers to. His message: I live among you by choice; I can leave if I want. But by November of 2011, near the end of Richard Beasley’s run, things are falling apart on both the bodily maintenance and criminal mastermind fronts. Rich has been dyeing his hair as part of his new identity, but now the filmy silver roots have grown out. He’s abandoned his house and is now living on the east side of Akron in a rented room that doesn’t even have a door you can close. A Tale of Two Dads: Mike Rafferty (left), with his son, Brogan, was a better but ultimately less formative father figure than Richard Beasley (right).

Photo: Courtesy of the subjects’ familiesBrogan will later say that he senses about Rich this morning a new kind of desperation. A more profound and disturbing desperation, if it’s possible to vibe more profoundly disturbing than this whole thing has been from the start. In less than a month, Brogan will deliver a series of lengthy confessions to the FBI about the elaborately planned but almost logic-defying crimes he and Rich committed together. If you listen to the confessions carefully, they begin to sound different when Brogan starts describing this morning’s events with Tim Kern. Throughout most of the hours of his statements, Brogan maintains a tone of almost stolid impassivity, sounding like someone who’d merely watched a series of killings on a strange unmarked videotape he received in the mail—what happened was awful, certainly, but concerned events that had nothing to do with him. But when he talks about Tim, it’s like things won’t stay psychologically tamped down.

It’s as if whatever mental box he’d built to house these events so they would be out of sight, on this day that box comes unsealed and everything hidden there spills out. There is a surveillance camera in the parking lot where Tim Kern is waiting in his 1995 Buick LeSabre. Footage from that camera will indicate it is five minutes after 6 A.M. On that morning of Sunday November 13, 2011, when Rich and Brogan arrive to get him.It is hard not to like Rich Beasley right away. When I first see him, sitting in navy prison pants in the visitors’ hall at Chillicothe Correctional Institution, which is situated in farmlands south of Columbus that are on this winter day frozen into a lifeless meringue, he stands and greets me with a commiserating smile that says: Can you believe it, the world is so fucked up, but did we really expect anything different? His hand is an old overboiled ham hock that envelops mine in a shake. He is large, with a fulsome white goatee and an untrimmed mustache that covers the absence of front teeth and works as a kind of flap behind which bites of microwave cheeseburger disappear as a dog disappears into a flap in a back door.

He has lively, kind of almondy-shaped blue eyes that do not shy from contact and don’t seem to have a thing in the world to hide. They might be said to have a mischievous twinkle. The hairs of the eyebrows are unruly and backward-reaching. He looks like the Grinch, or at least a little like he was drawn by a cartoonist.'

I have to admit I don’t get GQ magazine,' he says. 'I get Easyriders magazine and something called Armchair General, about military history. I also read The Week cover to cover every week.' It’s here, in the old death-row visitors’ wing at Chillicothe, a vast empty hall surrounded by two stories of Shawshank Redemption-vintage cells, that we speak for a total of about eight hours over two days. It’s easy to see that Rich was a preacher.

The man has the gift of gab. But he’s not what you’d call silver-tongued. His talent in the sermonizing arena was never soaring oratory, more of a folksy sociability. He can talk knowledgeably about using a store-bought still to make moonshine and the origin and bylaws of the Hells Angels, as well as how right Jesus was when he said to give unto Caesar what was Caesar’s. Rich says he always lived by the laws of God but that, when he went on the run from the law, he wasn’t living by the laws of man and that’s wrong, so shame on him.'

You seem like a guy people feel comfortable with,' I tell him.He releases another commiserating grin, this one called guilty as charged. 'People say that,' he replies.God has been the one constant in his life, he tells me, thanks to his mom.' I accepted Jesus as my savior when I was 12 years old,' he says.

'I was baptized then, and that’s all the baptizing I needed, according to my religion.' Rich’s original and most defining role in Brogan’s life was always: the guy who took him to church.

First as a good-works type of deal and then because they were homeys. Rich did his ministering in the ghetto, but he and Brogan went to services at the Chapel, a giant evangelical church that looks not unlike an aging community college and serves thousands of mostly middle-class parishioners who don’t fancy putting on airs when it comes to worship but value community and charity and Christ. Rich’s mother, Carol, has been a member in good standing at the Chapel for forty years.' I took him to church because he needed it,' Rich says. 'It was the right thing to do. His father would go to his bikers clubhouse on Friday and wouldn’t be home.

And his mother, well But Brogan loved church. That was his punishment—he wouldn’t be allowed to go to church.' 'He was 9, but he looked 14,' Nancy Wilson, one of the regular members of the Bible study, told me at a Panera Bread in Akron one morning last winter.

'Brogan was like a puppy. He was following Richard around.' And Rich, on the other hand: 'Well, he maintained what you call the rough look. You know, the down-and-outer look,' Nancy says. 'He was very disheveled, but he felt that gave him an ’in’ with the people he was ministering to.'

Nancy, and the whole Bible-study group, got to know Rich from the letters he sent his mom when he was doing some time in prison in the early 2000s. Carol would read the letters aloud, and then they’d pray for him. They’d heard, Nancy says, how he’d gotten in trouble the first time, down in Texas, when he wasn’t more than 25 years old. A series of robberies. Then a gun charge that he told everyone wasn’t his fault, and a couple of other scrapes that he explained were really just misunderstandings.

It did seem to Nancy that he spent a lot of his letters complaining about the bedding and the food and didn’t say too many remorseful things, but the group was compassionate, because give the guy a break, he was in jail, after all. Plus, they’d all do anything for Carol. She lived a real Christian life.

There wasn’t a thing she wouldn’t do or give to help people.And after he got out, Rich really seemed to have found his way back to God. He’d become a chaplain. Well, he hadn’t technically been ordained, but he said he was training up. The group knew all about that halfway house he’d started down on Yale Street, where he lived. There were some weird people who used to stay there, certainly. That one guy ended up being a sex offender. But these were Rich’s people—the downtrodden, the addicted, the half-wits, the streetwalkers, petty thieves, and wrecks of Akron.

He lived among them. Because that’s who needed help. 'We overlooked things,' Dave says now. We overlooked signals. They were there.'

There really is a plot of land down in Caldwell, just like Rich promised in the Craigslist ad. It technically belongs to a coal-mining company. It’s beautiful in that corner of Ohio’s Appalachia, the hillocks bunched up like geological bedcovers and frosted in woods. It feels like being back in what even people who have known no such simpler time refer to as a simpler time.If on this November morning you were to head out of Caldwell, up onto Rado ridge, past a couple of desolate houses, and turn onto Don Warner Road, you would find 'the farm.' That road will drop you down into what people here call a 'holler,' and if you stop midway down the hill and take the half-grown-over four-wheeler track, you would find a hole containing the body of one Ralph Geiger, naked and partly decomposed. Ralph Geiger being the name on Rich’s driver’s license and pill prescriptions these days. The body has been here since summer, when the leaves were green; now it sits beneath four feet of damp earth coursed by hunters out savoring the final days of bow-hunting season.

If you left the four-wheeler track and traveled farther downhill to the wooded floor of the holler, you would find under two feet of dirt the body of David Pauley, who’d answered the ad in October, when the leaves had begun to change. He’d driven up from Virginia with a pickup and a U-Haul filled with model trains, NASCAR memorabilia, a shotgun. Maybe fifty feet away from David Pauley’s body is a hole that Brogan had dug not much more than a week ago. It is empty except for several inches of rainwater—it had been meant for the body of Scott Davis, who’d answered the ad and decided to move all the way up from South Carolina. But with Scott something had apparently gone wrong with the gun. Rich had only been able to shoot Scott in the arm, and then Scott had taken off into the woods. Bleeding and cold, Scott hid in the underbrush for seven hours, until, after dark, he’d just by chance found the road again and walked until he found a house with a light on.

There’d been no gain from the failed commission of that crime, and that’s why Rich and Brogan are at it again so soon, in this parking lot at dawn, saying good morning to Tim Kern.Brogan says he hangs back while Rich does the interfacing with Tim. Rich gets jocular and street-preachery, and Tim yields. It is in keeping with Tim’s character. He is closing in on 50 years old and recently unemployed—he’d been working nights cleaning Speedway parking lots with these big Zamboni-like machines until he was recently downsized. He has a history of being a burner and a loafer and a dude who loves classic rock. He is the divorced father of three boys.

Tina, his ex-wife, a cocktail waitress at the Winking Lizard Tavern, still loves Tim, but she couldn’t take being married to him anymore. It was like having another kid. In the most recent photographs, his face reveals an almost boyish guilelessness that doesn’t age super well. Brogan thinks he seems sweet. Today he wears this black baseball hat that he can’t seem to put on straight.

Holes in the Woods: Rich wasn’t partial to physical labor, so Brogan did the digging. Photo: Courtesy of the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, BCIThe first fucked-up thing Brogan notices about the Tim Kern situation is the car. A Buick that can’t operate at speeds over thirty miles per hour. This is the big payday Rich has been hoping for? A car you can’t even drive on the highway?

There is no question about Tim taking it down to the 'farm'—they’ll take Brogan’s car. And then there’s the stuff. Tim is living in his car, at this point. All he has are garbage bags filled with clothes and keepsakes, a few pictures of his family, and a soiled ream of personal documents of the type you see the itinerant clutching outside government offices everywhere.

Before they get into the car, Rich starts telling Tim which of his things he’ll need down on the farm and what he should come back to pick up later. Take this, leave that. A toolbox, a believable amount of clothes, so Tim will think he’s really going somewhere. Brogan, as the muscle, grapples the TV into his trunk. It’s not even a flat-screen. Why does Rich want this TV?

What kind of vetting process could Rich have done on this guy? Whatever slim margin of logic they’ve been operating on, robbing and killing men who were themselves almost destitute, now it’s out the window. Rich asks Tim how much cash he has on him to get by with down on the farm, and Tim gets all sheepish and says: Five bucks. While it’s still dark, the three of them drive out of that parking lot and into the still-somnolent morning for what is supposed to be an hour-and-a-half drive to Caldwell. Rich and Brogan up front, with Tim in the back, like a kid.Rich keeps the patter up. He was always good like that. Brogan often remarked inwardly about how weird some of the stuff Rich talked to these men about was.

Rich would always take them out for breakfast on the way to the farm, the big magnanimous boss guy. When they were eating breakfast with David Pauley just before they killed him, Rich told this long story about a friend of his who looked like Kenny Rogers, and when they’d go out to eat, Rich would let it slip to the waiter that it really was Kenny Rogers and they’d all eat for free. Today, Tim Kern seems affable in the face of Rich’s small-talk fusillade, kind of dazy and trying to act professional around his new employer. 'Chaplain Rich' allegedly ran a prostitution ring out of the so-called halfway house (above), he operated in Akron.

Photo: Courtesy of writerWhat the Craigslist job offered Tim was an unforeseen opportunity: an actual grown-up life. Instant adulthood, including a place to live where his sons—they were grown, but he called them his 'babies'—could come visit, a setup that lately seemed beyond him to puzzle out. Still, Tim did not exactly go gladly into this adventure. He’d been anxious yesterday, wringing his hands, telling his boys he didn’t want to leave them, staying up all night packing at Tina’s house—he still used it as kind of a home base for showering and the keeping of important items. He was trying to seem laid-back about it, but he felt pretty adrift, heading out that morning to go live by himself on a farm in southern Ohio.Before they get too far, Rich leans back and says, Hey man, turns out we were hunting for squirrels out by the old Rolling Acres Mall the other day.

And you know what? I lost my watch. It’s got a lot of sentimental value. Do you mind if we go over to the woods and look for it real quick before we head down to the farm? And Tim says, No, I don’t mind.Granted, maybe Rich and Tim live in a world where it’s not totally implausible to have been hunting squirrels in the Akron suburbs. But it was still a weird thing to say.

This overly companionable aging biker type and his darkly silent 'nephew' pick you up to drive you down to your new job on a farm, but first, at six in the morning, they want to root around the woods for a watch—a watch!—they lost shooting at urban rodents the other day? But what would you say if you were Tim? One thing about humans is that they will put up with all but the most absurd and alarming events once they’ve signed on to a situation. There is in fact a moment when the teenage girl could jump out at the stoplight once she starts to get the smell of bad magic on the guy who said he’d give her a lift home, when the homeowner could close the door on the man at the front steps whose face isn’t composed right at all. But if you don’t bail right away, chances are you will be along for the entire ride, however windy and gruesome and never-ending it turns out to be.

We’ve all done it: taken the cab even though the driver seems weird, gotten on the plane even though that guy in the trench coat is sweating and talking to himself, stayed in a situation even though some tingly instinct is telling you to flee. And what you’ve learned from those experiences is that it always, always works out. Trust is how Craigslist works in the first place.

The shocking thing isn’t that the occasional bad actor on Craigslist shows up and takes advantage of that trust. The shocking thing about Craigslist is that it almost never happens. Tim Kern will not make it down to Caldwell today. He is not going to a desolate parcel of former strip-mining land carefully selected because it seemed like it might actually need a caretaker and because you can’t hear a gunshot from the nearest house. Tim Kern will never get farther than the scrub woods around an abandoned suburban shopping mall. This criminal enterprise is rapidly devolving, the standards lowering from a kind of wannabe Hollywood film about professional hit men into a haphazard, tragically absurd killing spree.

We know now that it will be over in a week. But to Brogan it seems like it could go on and on and on and on.

When he talks about it now, he says he was living in a state of total acquiescence. A surrender to what he calls darkness. The entire period suffused with a thick matter that fundamentally transformed all things, from the food he ate to the people he talked to, into some kind of intolerable simulacra that tasted of metal and death.When I meet Brogan last fall at the Warren Correctional Institution, he’s 18 years old and still looks older than he is. He wears his hair slicked back with product, comb marks visible, and a small trimmed mustache. He is fastidious, immaculate, his navy prison pajamas neat and creased. He does push-ups on his knuckles every morning, part of a fully regimented and scheduled day he once described in a letter: 'After returning from breakfast, I do my hygiene—brush my teeth, etc.

After that I try to straighten up the cell: make my bed, make coffee, fix the stuff on the floor' Two years ago, he had never even been in the back of a police car. Now, in the early days of a life sentence with no possibility of parole, he has already come to inhabit the persona of the old professorial prisoner who approaches life inside with a quiet, philosophical asceticism.'

No one knows how old I am in here because I’m old-school,' he tells me. 'I carry myself as if I were older. I look like I’m midtwenties. Plus, they all think I’m this crazy killer.

This serial killer. So they steer clear of me.' Brogan thanks me for coming, even though he gives the impression that he would rather be alone and is doing this because his father told him to. (Both Brogan and Rich are appealing their verdicts.) He refuses my offers of food and drink but eventually agrees to allow me to buy him a black coffee. He expresses disdain for the prisoners here who aren’t like that: 'People in jail, they come around asking for coffee or food or whatnot,' he says. 'No sense of shame, even if they don’t know you at all.

I would never do that. I would rather go without.' We sit across a short table from each other over the course of two days.

I knew he was going to be a quiet kid, but the way he’s quiet is different. When I ask if he once loved Richard Beasley, the pause is so long, Brogan gazing kind of inwardly in the midst of the heartbreaking human calamity that is the visitors’ room—shackled men with face ink and cornrows holding their newborn babies, old moms wheeling oxygen tanks to buy their only sons a microwavable calzone—that I’m not sure if I’m waiting for an answer or this is his way of saying 'Pass.' But it’s not the desperate quietude of someone who wants to connect and can’t figure out how. It’s an almost imperturbable sense of independence.

Brogan is, and always was, a priori different, is how he sees it. He’s not like me, he’s not like the kids in his high school class, he’s not like the man shackled with the neck ink, he has never been like anyone ever except maybe his dad and his mom, though both of them were always at distances so permanently untraversable that he couldn’t know for sure if he was like them or not. He has never really needed other people. (This is convenient, because he has never had anyone he could safely need.). 'Chaplain Rich' is shown here with Brogan in a restaurant surveillance video, getting a bite before an attempted murder.

Photo: Karen Schiely/Akron Beacon Journal/AP PhotoThe first time I met Mike Rafferty, Brogan’s dad, he was in his garage listening to Deep Purple, 'Smoke on the Water,' lifting weights on a quiet afternoon in his three-bedroom suburban ranch. Early fifties, small in stature, I’d guess five feet eight inches, built almost in a square, a Rubik’s Cube of flesh, with a long dark ponytail, a prominent forehead, a small expressionless mouth, and shiny dark eyes framed out by the longest, most beautiful, dark eyelashes that give a poignancy to the latent violence he exudes. It’s like My Little Pony was a 53-year-old biker from the rust belt of Akron. He is a machinist by trade, works nights precision-cutting metal for aircraft landing gear, and, yes, is the president and a member in good and legendary standing of the North Coast motorcycle club, a close affiliate of the Hells Angels. According to police, North Coast is suspected of dealing in meth, but Mike has no criminal record, save for a public-urination charge, and strikes me, while he sits on his sofa in jean shorts and a tank top, as a straight arrow who does not suffer fools gladly or without punching them in the face.' Maybe I wasn’t the kind of father I should have been,' he says. 'I wasn’t real good at showing emotion, and I was a bit of a disciplinarian.'

The kind of father he was: the kind who buys a small house in a good school district, teaches his kid to box in the garage starting when he’s 5; who didn’t drink on weeknights but spent Fridays at 'church' (the weekly meeting of North Coast) and most of the weekend at bars; who, Brogan says, once broke the boy’s nose over a missing report card; who Rich and Brogan and Yvette, Brogan’s mother, all agree was a good provider but terrified Brogan. From Mike, Brogan learned what Mike saw as that most important tool: self-reliance. To be able to take care of yourself in a fight, to get yourself to school, to keep a straight house and get good grades, to understand never to make excuses or dwell on how hard it all is.

Up until that November, Mike saw himself as a biker-machinist dad who was doing a pretty good job raising a boy more or less on his own. It was a stable place to live, but not a home that allowed for certain parts of being a kid: like admitting that you’re weak, and you don’t have the answers, and that circumstances can arise that you simply cannot be expected to take care of by yourself. Brogan’s mother, on the other hand, is an addict. Over time, he’d reduced his relationship with her to the smallest unit of parenting she could handle: Brogan told Yvette she could go on a crack binge—because no matter what she promised, she was going to go on a crack binge anyway—she just couldn’t do it on the weekends Brogan was with her.

But he couldn’t rely on even that.I met Yvette for dinner this past winter. Yvette was a biker chick from the first time she ever got on the back of a motorcycle. 'I was hot as shit, I ain’t gonna lie,' she told me over steak at TGI Fridays. 'Hair down to my ass. By all accounts this description of Yvette Rafferty is accurate. She arrived in northern Ohio from out of the American South as a woman from a dream issue of Easyriders magazine, skinny and willowy, with hair spun from ice cream and sunshine and a taste for denim and leather.

She liked to party, and she was crazy, too. She once rode a big old dirt bike that belonged to a Mexican all the way back from Daytona Beach while the bike’s owner leaned back and slept against the luggage rack. And she ain’t never even rode a dirt bike before! She met Mike when she was working at a bikini bar. That was not long before she became addicted to cocaine. She says she was sober while she was pregnant.

But Brogan wasn’t 3 days old when she disappeared into a crack house with him still swaddled in a hospital blanket. Mike took Brogan away after that, and they separated. She still seems like kind of a love mama, even though a good chunk of her humanity appears to have disappeared into addiction. She is a hug person, a kiss person, a person who loves to cry, the type of hippie biker chick who’d want to sleep with all her babies in a big family bed but also bungee them to a chopper for a ride to get formula. But in reality she is now a 49-year-old woman who has to remove her new dentures before she eats a TGI Fridays steak with Jack Daniel’s sauce. Who, after two beers, starts shivering and loses the gift of coherent speech for long stretches and tries to eat a wet nap off her plate.

Sits there chewing it like lettuce until I reach into her toothless mouth before she can swallow it. Brogan has known before memory that his mother is an addict. When he was 10, he found evidence on the Internet that she’d prostituted herself. The really terrible moments of my dinner with her came when she admitted knowing what she’d become. Her face crumpled and she said: 'I know all this is my fault.

I know it is. If I hadn’t have been an addict, none of this would have happened.' 'To me, he was just death,' Brogan tells me.

'When I thought of him, it was death.' Rich was death incarnate?' Rich must have known, somehow, that Brogan could handle living through that darkness without imploding. It was Rich’s gift to see potential where others do not, where most people would not want to look for potential. Rich was almost blinded by the opportunities he saw—like growing weed or making moonshine or faking a raffle or trading on the inherent advantages of running a 'halfway house' in the hood—in a way that seemed to make normal opportunity almost invisible to him. What Mike, Brogan’s dad, used to say about Rich was that he’d rather make a crooked nickel than an honest dollar.

It was the kind of thing you could say right to Rich’s face and he’d laugh about it. Mike says Rich once asked him if he’d like to rob a bank. Which Mike most certainly didn’t want to do.

But those were the kinds of things kicking around in Rich’s head. It’s my theory that Rich saw in Brogan a kind of potential that Brogan was probably unaware of. Rich knew Mike from the world of Akron bikers, and Yvette from a life that brought him into the drug houses and jails of Akron, and he knew Brogan. This hulking castoff of a kid, who strangers thought was possibly mute but confidants knew as a preternaturally sardonic kid who acted like a full-grown man but was probably hiding a stunted little baby somewhere inside, like a worm larva in the middle of an apple.

I’m not saying that Rich became friends with Brogan when he was 9 as part of a long con. Rich probably started taking Brogan to church because it felt like a good Christian thing to do.

Rich seemed to genuinely enjoy hanging out with Brogan, tooling around Akron, visiting historic graveyards and dropping general world knowledge. And in the bargain Brogan, according to the amateur psychology of pretty much everyone who came into contact with them, got a dad who wasn’t a hard-ass, who took him around and treated him like an equal, but who also understood (without judgment) the world where his mom came from, a secret he didn’t much share with his friends from school. Yvette describes Brogan’s feelings this way: 'Brogan was ashamed of me, but he loved me.' Rich was kind of like Brogan himself—they both straddled the straight world and the world of the street. And when the time came, Rich knew what Brogan’s skill set might be, knew how to activate it, and he apparently didn’t hesitate. In the summer of 2011, before they lured that first man, Ralph Geiger, down to southern Ohio, Rich had a conversation with Brogan. There was going to be a warrant out for Rich’s arrest.

And if they got him, he said, they were going to put him away for a crime he didn’t commit. So he was going to go on the run. This news lit in Brogan an incandescent bloom of indignation that in the mind of a 16-year-old can glow so much more purely than in people like you or me.

The damn cops, he knew about them, they messed with his mother.' Well, he had told me this story about how they were going to put him in jail over some old stuff that he didn’t do,' Brogan says. 'I was angry.

It didn’t seem right.' But then, when the murders began, it couldn’t have been just about that anger anymore. Whatever compelled Brogan to help Rich, it had to have become something else. Brogan says now that he did what Rich said because Rich threatened him.

He told Brogan: I know where your mother lives. I know where your sister lives. He would check on Brogan every day, call him, have him meet up. Brogan says that every time he dug a hole, he expected that he might end up in it. This explanation seems too simple to me, but Brogan’s is the only narrative we have about these events.Threatened or not, Brogan trudged on. Like a golem. Made of clay by his master, animate but not awake to his humanity.

To be there and not really be there, the way he is when we are at the Warren Correctional Institution, that was what Brogan could do better than just about anyone. I would say that Brogan’s greatest skill as accomplice in a crime of massively gruesome proportions is to be able to locate himself fathoms beneath the emotional sea even when he’s right beside you.

Does Rich see himself as a man attuned to the potential lurking in places other men would never look? I try to broach the topic when I meet him on death row. I ask about the warrant that had been out for his arrest, which was for, essentially, running a prostitution ring—twenty women, one male—out of his 'halfway' house.

A prostitution ring staffed by the women he ministered to. The women for whom he’d stood up in court to promise judges that, as counselor and halfway-house proprietor, he’d look after them. The women he’d visit in jail, talk on jailhouse phones with, and describe his physical longing for in conversations the authorities were recording. By most accounts, his favorite had been a 17-year-old girl named Savannah, who died of an overdose. Brogan knew her as Rich’s girlfriend.I tell Rich that I interviewed one of these women, Amy Saller. She told me, I say, that you did try to get her off drugs, in a way.

She said you had devised your own detox system: three rocks one day, and then two for each of the next couple of days, and then down to one. But it never worked. So you’d just buy her the rocks and let her smoke them at your place. She thought your biggest fear was that she would leave, and you wanted her near you. Sure, you wanted to trick with her sometimes, but she seemed to feel she had you in her back pocket.

She knew she could steal from you and you might yell and scream, but you weren’t going to get violent. She said you put her up as an escort on Backpage and took a commission on the money she made. It was strange that Amy, whom you pimped out, who has in the intervening months gotten sober and is working at Red Lobster now and has earned the right to visit her kid, talks as if she isn’t totally sure who was using whom. When I ask you about all of the above, your answer is only: 'Amy Saller. I’m sorry, I don’t know who that is.' And about the notion of those physical longings and the like: 'I haven’t been able to have sex since I had my car accident,' Rich tells me.

He’s referring to an accident he had about eight years ago. 'I had a steel coffee cup in my lap when it happened.' He smiles mischievously here and slits his eyes like a cat. 'You can’t use what you don’t have.' And then, thinking about it, he gets a little more grandiose. 'I think it was a blessing from God that I wasn’t able to have sex.

If I could, it might have complicated the relationship I had with all those women. I might have been tempted.

But as it was, I was able to remain pure.' On the way to the Rolling Acres Mall, Tim mentions that he likes Brogan’s Buick. Rich has a plan for Tim’s car: He and Brogan will come back with some blowtorches and scrap the car themselves for cash. Rich will take the cash and give Tim a Ford F-150. A more appropriate vehicle for the terrain down on the farm. Tim will pay off the difference in installments that will come out of his wages. It’s almost as if Rich enjoys spinning out these scenarios, a natural outgrowth of the fecundity of his scheming brain—he’s got the gift, so why not just share it with the world?Rolling Acres is Chernobyl-y, with its cheerful awnings inviting you to condemned movie theaters and the now removed names of big-box stores silhouetted onto the brickwork of its entrances.

The mall was built in the ’70s and expanded in the ’80s, and now, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, is home to only a single JCPenney outlet store that will itself soon be shuttered. They pull around an outbuilding and park near the woods.When they brought men to 'the farm,' Rich had a trick he’d pull. He’d walk in front of the subjects right away and let them follow him down one of the tracks into the forest.

Having a stranger walking behind you into the woods tends to raise defenses. And then at some point—like in Scott Davis’s case, when they were looking for some construction equipment they couldn’t find—there’d be an excuse to turn around. And just like that, the subject would be out in front. That’s when Rich would shoot him in the head without the victim ever knowing what happened, Brogan says. It was the beauty of Rich’s method that he never had to lay a hand on anyone, never had to overpower a body—he simply had to pick the right people and then be the guy in charge.And now they are in the woods, looking for this 'watch.'

Rich pulls back a branch and lets it slap back at Brogan and Tim. Then Tim holds it back for Brogan so he can walk. This act of kindness disturbs Brogan, though he doesn’t say anything.Rich and Tim walk together, looking. Brogan acts like he’s searching the thick November leaf layer a few yards away. Brogan says he hears a pop.

When he turns, he sees that Tim is down on his knees and Rich has the.22 in his hand. Tim’s holding the side of his head. And then Rich says, 'Are you all right?' Like he’s concerned Tim’s hurt himself. But when Tim doesn’t respond, Rich shoots him again, and again, and again, and Tim slumps over onto his side.

There’s something wrong with the gun, Rich is saying. And it hits Brogan then that Tim is still breathing. All of these events, Brogan says, they blend together—maybe because he has a powerful reluctance to go back over them or because he dissociates even right there in the moment.

But this whole debacle is beyond the pale, horrific in an absurd, intolerable way to Brogan. This man has nothing worth stealing, there is no reason to kill him. And now he won’t die. Rich gets up close and shoots him a last time, in the face. Now Tim is lying on the ground, eyes open wide and staring at the leafless branches above.

Every few seconds he takes a big, audible gulp of air, like a dying fish. He’s still alive, Brogan says, he’s still alive. Rich says no. His brain is dead, there are four bullets in his head and I put one between his eyes. It stops eventually, the desperate, drowning sounds.

Then Rich says to grab a leg and takes the other one himself. And together they drag Tim to the hole.

It’s only two feet deep, and Tim doesn’t completely fit in there. But Rich doesn’t seem to care. He removes Tim’s jacket and cuts the shirt off with a pair of scissors.

That black hat he kicks to the side—it’s covered in blood.Why? Brogan says he asks Rich.

Why did we do this, he didn’t have anything. Rich has his own logic about it: Well, he was a dead man as soon as he got in the car. As if it had been out of their hands. Richard Beasley.

Photo: Karen Schiely/Akron Beacon Journal/AP PhotoThe first time, with Ralph Geiger, they removed all the clothes, covered him with lime, replaced the ground cover so you could have walked right over the grave and you wouldn’t have suspected anything. For David Pauley, they had changes of boots, gloves; Rich had even put a $20 bill next to the hole so they’d know if anyone saw the hole in the interim. But by the time they got to Tim Well, Tim is still in his pants and shoes and socks.

Brogan isn’t even finished backfilling the hole when Rich tells him to stop. It’s getting light out now. Rich is ready to get out of here. He starts kicking some leaves over the hole.This would be the last murder. Scott Davis had gotten away. And he talked to the police.

Right now, as Brogan and Rich are at the mall, the FBI is tracing the Craigslist ad back to Rich’s IP address, and later to a camera at a Shoney’s in Marietta, Ohio, that snapped a picture of Brogan and Rich as they walked in to meet Scott Davis the morning he was shot. Three days from now, agents will show up at Stow high school and pull Brogan from class. He will still have the TV in his trunk. He and Rich won’t even have scrapped Tim’s car yet—there will have been functionally zero financial or other gain from the murder of Tim Kern. The same day Brogan is arrested, a SWAT team will pick up Rich outside the house where he rented the room.

There will be a helicopter and everything. It’s getting lighter out as they drive back from Rolling Acres.

Rich has Brogan stop at McDonald’s for breakfast. Rich likes McDonald’s because of the free Internet. Brogan says they don’t speak. Rich taps on his computer, and Brogan watches the street outside as the day gets brighter.

He drops Rich at his place and heads for his mom’s. When he’s pulling up the hill toward home, he gets a call from Yvette on his cell.

She’s crying. A man she knows—the guy she calls her 'millionaire maniac,' a 'famous' dog breeder, known for his prize German shepherds, who likes to party—had been an asshole last night, and now she is walking home. Brogan doesn’t say much, just that he’ll pick her up on the way home. She’s still crying when she gets into the passenger seat. This is one of those periodic moments of clarity for her, when she can see plainly what the dynamic is with her son, Brogan being the stable one, the guy who comes to the rescue. I’m sorry I wasn’t there last night, she says, I didn’t know you were coming over this weekend, I swear. Brogan stops her.

It doesn’t matter, Mom. It really doesn’t matter.A few months before I go to Chillicothe to meet Rich, I have breakfast with Carol Beasley, Rich’s mom, at a bakery near her house. She is a kind woman in a cute Christmas sweater who is befuddled by her own cell phone and is more worried about the weather for my flight back to New York than I am. Carol tells me that she doesn’t want to fool herself.

Richard probably did the things they say he did. Though she can’t help slipping into the framework Rich has provided her for these events—the inconsistencies, the suggestion of plots underlying the apparent facts.

'But why did Scott Davis make the ambulance take him to Akron General hospital, which is right by the motorcycle club?' 'He literally had to pass several other hospitals on his way there. And why did Scott refuse to talk to the police for days?'

We have a philosophical conversation about how, even if she pretty much knows the truth, she won’t really be able to process it until Rich admits it. I tell her that I’ve exchanged some letters with him in advance of our meeting. I told him I was hoping that he would be able to fully open up, to come clean. No one will really know what happened until he does. My guess is that it won’t change the facts. But it seems impossible to understand this whole saga without knowing the truth from Rich—why he decided to do this, what he thought as he slept in the same hotel room with Ralph Geiger the night before he murdered him. Surviving Prison: 'I carry myself as if I were older,' says Brogan, pictured here in court with his mom, Yvette.

Photo: Phil Masturzo/Akron Beacon Journal/AP PhotoIt’s also true that there are things we don’t know about Brogan. He claims he participated in these crimes because Rich overtly threatened him. I think it’s also possible that Brogan participated because he thought he needed to be a man. But even if Brogan is lying about the threats, even if he believes that he did this of his own free will, I think it was still, functionally, coercion. These murder-robberies benefited only one person: Richard Beasley. There was some discussion at the trial about how Brogan received treasure from these men: David Pauley’s shotgun, etc. But that fact strikes me more like, for instance, an uncle who has molested his nephew and then buys him anything he wants at the toy store, and in so doing binds all kinds of incompatible emotions (shame, guilt, pleasure, terror, pain) into a terrible cocktail that can never be unmid.

Regardless, I tell Carol that morning that I hope Rich can tell the whole truth, because it’s the only possible way to take even a fractional step toward making amends.' Oh,' Carol Beasley says, the shiny tinsel threads in her sweater throwing plasticky sparks beneath the recessed lighting, 'I don’t think so. He doesn’t want anyone to know the real him. He never has.

He’s too ashamed. He will never, ever do that.' And she was right. The moment he sat down across the table from me, with that twinkle in his eye, Rich began telling magnificent stories. Ralph Geiger had been down in Caldwell, 'pounding nails' for work, when he came across a meth lab he shouldn’t have seen, and the meth dealers had to walk him out into the woods and kill him.

Brogan murdered Tim Kern himself, with an accomplice, as a way to earn his colors in the North Coast motorcycle club. Rich seemed to understand that some of this was hard to believe, and so he didn’t gild the lily. When we came to a fact that didn’t make sense, he made like the two of us were trying to piece this whole mystery together, but he could only help me so much. 'I don’t know,' he’d say, staring off at a section of floor fifteen feet away, as if examining some mysterious half-human creature who’d been following him at this distance for quite some time. 'That’s what I’m trying to figure out.

I don’t know.' But he did not confess to a thing. Near the end of our conversations, I ask him a little bit about religion. Because it would seem that this failure to come clean would probably have some ramifications with God, if Rich happened to believe in God.How is it a fellow gets to heaven?' I believe you will go to heaven if you accept Jesus Christ into your heart as your savior.'

You don’t have to confess to anyone?' You have to confess to God and ask forgiveness.

Do you know the story of King David? You’re of Jewish descent, right? He killed a man and had an adulterous affair. And he was the apple of God’s eye.' Confess to God and then you’re in heaven?He nodded.

Audio: Listen to this story. To hear more feature stories,Thomas Hargrove is a homicide archivist.

For the past seven years, he has been collecting municipal records of murders, and he now has the largest catalogue of killings in the country—751,785 murders carried out since 1976, which is roughly twenty-seven thousand more than appear in F.B.I. States are supposed to report murders to the Department of Justice, but some report inaccurately, or fail to report altogether, and Hargrove has sued some of these states to obtain their records. Using computer code he wrote, he searches his archive for statistical anomalies among the more ordinary murders resulting from lovers’ triangles, gang fights, robberies, or brawls. Each year, about five thousand people kill someone and don’t get caught, and a percentage of these men and women have undoubtedly killed more than once.

Hargrove intends to find them with his code, which he sometimes calls a serial-killer detector. Hargrove created the code, which operates as a simple algorithm, in 2010, when he was a reporter for the now defunct Scripps Howard news service. The algorithm forms the basis of the Murder Accountability Project ( MAP), a nonprofit that consists of Hargrove—who is retired—a database, a, and a board of nine members, who include former detectives, homicide scholars, and a forensic psychiatrist.

By a process of data aggregating, the algorithm gathers killings that are related by method, place, and time, and by the victim’s sex. It also considers whether the rate of unsolved murders in a city is notable, since an uncaught serial killer upends a police department’s percentages. Statistically, a town with a serial killer in its midst looks lawless. In August of 2010, Hargrove noticed a pattern of murders in Lake County, Indiana, which includes the city of Gary. Between 1980 and 2008, fifteen women had been strangled. Many of the bodies had been found in vacant houses. Hargrove wrote to the Gary police, describing the murders and including a spreadsheet of their circumstances.

“Could these cases reflect the activity of one or more serial killers in your area?” he asked.The police department rebuffed him; a lieutenant replied that there were no unsolved serial killings in Gary. (The Department of Justice advises police departments to tell citizens when a serial killer is at large, but some places keep the information secret.) Hargrove was indignant. “I left messages for months,” he said. “I sent registered letters to the chief of police and the mayor.” Eventually, he heard from a deputy coroner, who had also started to suspect that there was a serial killer in Gary. She had tried to speak with the police, but they had refused her.

After reviewing Hargrove’s cases, she added three more victims to his list.Four years later, the police in Hammond, a town next to Gary, got a call about a disturbance at a Motel 6, where they found a dead woman in a bathtub. Her name was Afrikka Hardy, and she was nineteen years old.

“They make an arrest of a guy named Darren Vann, and, as so often happens in these cases, he says, ‘You got me,’ ” Hargrove said. “Over several days, he takes police to abandoned buildings where they recover the bodies of six women, all of them strangled, just like the pattern we were seeing in the algorithm.” Vann had killed his first woman in the early nineties.

In 2009, he went to jail for rape, and the killings stopped. When he got out, in 2013, Hargrove said, “he picked up where he’d left off.”. Researchers study serial killers as if they were specimens of natural history. One of the most comprehensive catalogues is the Radford Serial Killer Data Base, which has nearly five thousand entries from around the world—the bulk of them from the United States—and was started twenty-five years ago by Michael Aamodt, a professor emeritus at Radford University, in Virginia. According to the database, American serial killers are ten times more likely to be male than female. Ray Copeland, who was seventy-five when he was arrested, killed at least five drifters on his farm in Missouri late in the last century, and is the oldest serial killer in the database.

The youngest is Robert Dale Segee, who grew up in Portland, Maine, and, in 1938, at the age of eight, is thought to have killed a girl with a rock. Segee’s father often punished him by holding his fingers over a candle flame, and Segee became an arsonist. After starting a fire, he sometimes saw visions of a crimson man with fangs and claws, and flames coming out of his head. In June of 1944, when Segee was fourteen, he got a job with the Ringling Brothers circus. The next month, the circus tent caught fire, and a hundred and sixty-eight people were killed.

In 1950, after being arrested for a different fire, Segee confessed to setting the tent ablaze, but years later he withdrew his confession, saying that he had been mad when he made it.Serial killers are not usually particularly bright, having an average I.Q. Of 94.5, according to the database. They divide into types. Those who feel bound to rid the world of people they regard as immoral or undesirable—such as drug addicts, immigrants, or promiscuous women—are called missionaries. Black widows kill men, usually to inherit money or to claim insurance; bluebeards kill women, either for money or as an assertion of power. A nurse who kills patients is called an angel of death.

A troller meets a victim by chance, and a trapper either observes his victims or works at a place, such as a hospital, where his victims come to him.The F.B.I. Believes that less than one per cent of the killings each year are carried out by serial killers, but Hargrove thinks that the percentage is higher, and that there are probably around two thousand serial killers at large in the U.S. “How do I know?” he said. “A few years ago, I got some people at the F.B.I. To run the question of how many murders in their records are unsolved but have been linked through DNA.” The answer was about fourteen hundred, slightly more than two per cent of the murders in the files they consulted. “Those are just the cases they were able to lock down with DNA,” Hargrove said.

“And killers don’t always leave DNA—it’s a gift when you get it. So two per cent is a floor, not a ceiling.”Hargrove is sixty-one. He is tall and slender, with a white beard and a skeptical regard. He lives with his wife and son in Alexandria, Virginia, and walks eight miles a day, to Mount Vernon or along the Potomac, while listening to recordings of books—usually mystery novels. He was born in Manhattan, but his parents moved to Yorktown, in Westchester County, when he was a boy. “I lived near Riverside Drive until I was four,” he said. “Then one day I showed my mom what I learned on the playground, which is that you can make a switchblade out of Popsicle sticks, and next thing I knew I was living in Yorktown.”Hargrove’s father wrote technical manuals on how to use mechanical calculators, and when Hargrove went to college, at the University of Missouri, he studied computational journalism and public opinion.

He learned practices such as random-digit-dialling theory, which is used to conduct polls, and he was influenced by “Precision Journalism,” a book by Philip Meyer that encourages journalists to learn survey methods from social science. After graduating, in 1977, he was hired by the Birmingham Post-Herald, in Alabama, with the understanding that he would conduct polls and do whatever else the paper needed. As it turned out, the paper needed a crime reporter. In 1978, Hargrove saw his first man die, the owner of a convenience store who had been shot during a robbery. He reported on a riot that began after police officers shot a sixteen-year-old African-American girl.

Once, arriving at a standoff, he was shot at with a rifle by a drunk on a water tower. The bullet hit the gravel near his feet and made a sound that “was not quite a plink.” He also covered the execution of a man named John Lewis Evans, the first inmate put to death in Alabama after a Supreme Court abrogation of capital punishment in the nineteen-sixties and seventies. “They electrocuted people in Alabama in an electric chair called the Yellow Mama, because it was painted bright yellow,” Hargrove said.

“Enough time had passed since the last execution that no one remembered how to do it. The first time, too much current went through too small a conduit, so everything caught fire. Everyone was crying, and I had trouble sleeping for days after.”. In 1990, Hargrove moved to Washington, D.C., to work for Scripps Howard, where, he said, “my primary purpose was to use numbers to shock people.” Studying the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File—“where we will all end up one day,” Hargrove said—he noticed that some people were included for a given year and dropped a few years later: people who had mistakenly been declared dead. From interviews, he learned that these people often have their bank accounts suddenly frozen, can’t get credit cards or mortgages, and are refused jobs because they fail background checks. Comparing a list of federal grants for at-risk kids in inner-city schools against Census Bureau Zip Codes, he found that two-thirds of the grants were actually going to schools in the suburbs.

“He did all this through really clever logic and programming,” Isaac Wolf, a former journalist who had a desk near Hargrove’s, told me. “A combination of resourceful thinking and an innovative approach to collecting and analyzing data through shoe-leather work.”In 2004, Hargrove was assigned a story about prostitution. To learn which cities enforced laws against the practice and which didn’t, he requested a copy of the Uniform Crime Report, an annual compilation published by the F.B.I., and received a CD containing the most recent report, from 2002.

“Along with it, at no extra cost, was something that said ‘S.H.R. 2002,’ ” he said. It was the F.B.I.’s Supplementary Homicide Report, which includes all the murders reported to the Bureau, listing the age, race, sex, and ethnicity of the victim, along with the method and circumstances of the killing.

Hargrove began by requesting homicide reports from 1980 to 2008; they included more than five hundred thousand murders. At the start, he knew “what the computer didn’t know,” he said. “I could see the victims in the data.” He began trying to write an algorithm that could return the victims of a convicted killer. As a test case, he chose Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer, who, starting in the early eighties, murdered at least forty-eight women in Seattle, and left them beside the Green River.

Above his desk, Hargrove taped a mugshot of Ridgway in which he looks tired and sullen. Underneath it, he wrote, “What do serial victims look like statistically?”Creating the algorithm was laborious work.

“He would write some code, and it would run through what seemed like an endless collection of records,” Isaac Wolf told me. “And we did not have expensive computer equipment, so it would run for days. It was sort of jerry-rigged, Scotch-Taped.

He was always tinkering.”.Ridgway was eventually identified by DNA and was arrested in 2001, as he was leaving his job at a Kenworth truck plant, where he had worked as a painter for thirty-two years. He told the police that strangling women was his actual career. “Choking is what I did, and I was pretty good at it,” he said. Ridgway’s wife—his third—was astonished to find out what he had done. They had met at a Parents Without Partners gathering and had been married for seventeen years.

She said that he had always treated her like a newlywed. Ridgway had considered killing his first two wives but decided that he was too likely to get caught. Mostly, he killed prostitutes, and, if he killed one who had money on her, he regarded it as his payment for killing her. Hargrove began each day with a review of what had failed the day before. He sorted the homicides by type, since he had been told that serial killers often strangle or bludgeon their victims, apparently because they prefer to prolong the encounter. He selected for women, because the F.B.I. Said that seventy per cent of serial-killer victims are female.

Each test took a day. He had no idea if anything would work. For a while, the only promising variable seemed to be “failure to solve.” “After a hundred things that didn’t work, that worked a little bit,” Hargrove said, holding his right thumb and forefinger close together.

“I started making the terms more specific, looking at a group of factors—women, weapon, age, and location.”With those terms, the algorithm organized the killings into approximately ten thousand groups. One might be: Boston, women, fifteen to nineteen years old, and handguns.

Another might be: New Orleans, women, twenty to fifty, and strangulation. Since “failure to solve” had produced results, even if feeble, Hargrove told the computer to notify him of places where solution rates were unusually low. Seattle came in third, with most of the victims women whose cause of death was unknown—unknown because the bodies had been left outside and sufficient time had passed that the coroners could no longer determine how they had died. The computer, Hargrove knew, had finally seen Ridgway’s victims.By reading meaning into the geography of victims and their killers, Hargrove is unwittingly invoking a discipline called geographic profiling, which is exemplified in the work of Kim Rossmo, a former policeman who is now a professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Texas State University. In 1991, Rossmo was on a train in Japan when he came up with an equation that can be used to predict where a serial killer lives, based on factors such as where the crimes were committed and where the bodies were found.

As a New York City homicide detective told me, “Serial killers tend to stick to a killing field. They’re hunting for prey in a concentrated area, which can be defined and examined.” Usually, the hunting ground will be far enough from their homes to conceal where they live, but not so far that the landscape is unfamiliar. The farther criminals travel, the less likely they are to act, a phenomenon that criminologists call distance decay.

Rossmo has used geographic profiling to track terrorists—he studied where they lived, where they stored weapons, and the locations of the phone booths they used to make calls—and to identify places where epidemics began. He also worked with zoologists, to examine the hunting patterns of white sharks. Recently, Rossmo studied where the street artist Banksy left his early work, and found evidence to support the British Daily Mail’s assertion, made in 2008 but never corroborated, that Banksy is a middle-aged man from Bristol, England, named Robin Gunningham.“In a murder investigation, when you step away from the Hollywood mystique, it’s about information,” Rossmo told me. “In any serial-murder case, the police are going to have thousands and thousands, even tens of thousands, of suspects.” In the Green River case, the police had eighteen thousand names. “So where do you start? We know quite a lot about the journey to a crime.

By noting where killings took place or the bodies were discovered, you can actually create probability distributions.” In his book “Geographic Profiling,” Rossmo notes research that found, among other things, that right-handed criminals tend to turn left when fleeing but throw away evidence to the right, and that most criminals, when hiding in buildings, stay near the outside walls. Using computers to find killers has historical precedent.

Eric Witzig, a retired homicide detective and a former F.B.I. Intelligence analyst who is on MAP’s board, worked on the F.B.I.’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, Vi CAP, which was started by a Los Angeles homicide detective named Pierce Brooks. Witzig told me how, in the fifties, Brooks worked on the case of Harvey Glatman, who became known as the Lonely Hearts Killer. Glatman was a radio-and-TV repairman and an amateur photographer who would invite young women to model for him, saying that the photographs were for detective magazines. He would tie his victim up for the shoot, and then never remove the bonds. “The victim, a young woman, was not just tied up, but the turns of the bindings were sharp and precise, indicating that the offender took a lot of pleasure in it,” Witzig said.Brooks started to research the way that some killers seemed to commit the same crime repeatedly. He began putting all his murder records onto three-by-five cards, and after becoming interested in computers in the late nineteen-fifties he asked the L.A.

Police department to buy him one. He was told that it was too expensive. In 1983, he presented the idea of a homicide-tracking computer database to Congress, after which the F.B.I. Offered him a job at Quantico and bought him the equipment to start Vi CAP. The program was meant to be an accessory to investigations, but detectives didn’t take to it.

“The first and maybe main problem was the original Vi CAP reporting form,” Witzig said. Brooks wanted to record every element of a homicide and, as a result, there were more than a hundred and fifty questions. “Of course, there was user resistance,” Witzig said. “No one wanted to do more paperwork.” He added that the program had “some of the brightest law-enforcement deep thinkers in the world involved, but we exist at MAP because they failed.”M AP has its own limitations. Since the algorithm relies on place as a search term, it is blind to killers who are nomadic over any range greater than adjacent counties. There is also a species of false positive that Hargrove calls the Flint effect: some cities, such as Flint, Michigan, are so delinquent in solving murders that they look as if they were beset by serial killers.Someone versed in statistics can run the algorithm, which appears on MAP’s Web site. The rest of us, who might, for example, wish to know how many killings are unsolved where we live, can use the site’s “search cases” function.

Deborah Smith, who lives in New Orleans, is a hobby MAP searcher and a forum moderator on Websleuths, an online watering hole for amateur detectives. “I keep spreadsheets of murdered and missing women around the country, with statistics, and I highlight murders that I think might be related,” she told me. “I have them for nearly every state, and that comes from MAP. If I have a killer, like, say, Israel Keys, who was in Seattle about fifteen years ago, I’ll look up murders in Seattle and parts of Alaska, because he lived there, too, and see if there were any the police might have overlooked.” She added, “ MAP is just extremely, extremely useful for that. There isn’t really anything else like it.”MAP’s board hasn’t determined what to do with the algorithm’s findings, however, and the question presents moral and practical difficulties for Hargrove.

“We have to figure out our rules of engagement,” he told me. “Under what scenario do we start calling police?” A few months ago, Hargrove informed the Cleveland police that there appeared to be about sixty murders, all of women, that might involve a serial killer, or, from the range of methods, perhaps even three serial killers. Twelve of the women had convictions for prostitution, and their bodies were found in two distinct geographic clusters. Hargrove can’t say anything about his exchange with the Cleveland police, because MAP’s rules dictate that such communications are privileged.

The police wrote me that, as a result of Hargrove’s analysis, “a small taskforce is being considered to look at several unsolved homicides.” The head of the department’s special-investigations bureau, James McPike, the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, of MAP, “We’re going to be working with the group to help us identify what we might be able to do.”Hargrove is pleased about the investigation but he also worries that something may go awry. “What if they arrest the wrong guy, and he sues?” he asked. “I contacted a bunch of police departments in 2010, when I was a reporter, because I wanted to see if the algorithm worked.

Now I know it works—there’s no question in my mind. In certain places, we can say, ‘These victims have an elevated probability of having a common killer.’ In 2010, though, I had a big media company behind me, with lawyers and media insurance. Now I’m a guy with a nonprofit that has fourteen hundred dollars in the bank and a board of nine directors and no insurance.”One of MAP’s most public benefits has been making people aware of how few murders in America are solved. In 1965, a killing led to an arrest more than ninety-two per cent of the time. In 2016, the number was slightly less than sixty per cent, which was the lowest rate since records started being kept. Los Angeles had the best rate of solution, seventy-three per cent, and Detroit the worst, fourteen per cent. As Enzo Yaksic, a MAP board member and the director of the Northeastern University Atypical Homicide Research Group, told me, the project “demonstrates that there’s a whole population of unapprehended killers that are clearly out there.”.

Another of MAP’s board members, Michael Arntfield, is a professor at the University of Western Ontario, where he runs a cold-case society. It is focussing on the largest finding of the algorithm, a collection of a hundred unsolved murders of women in the Atlanta area over forty years.

Most of the victims were African-American, and all were strangled. From the Atlanta police, Arntfield got names for forty-four of the women, and has been learning more about them.

(Studying the backgrounds of murder victims in the hope of discovering how they met their killers is a discipline called victimology.) Arntfield and his colleagues separated the victims into two groups: a small group of older women, who were killed in their homes, and a larger group of young women, many of whom may have been prostitutes. From newspaper accounts, Arntfield has found two men who have committed crimes with strikingly similar attributes, both of whom are already in prison. Adam Lee, the head of Atlanta’s Major Crime Section, which includes homicide, told me that the police haven’t yet linked these murders to a particular killer, but he said that he considers MAP a useful tool and is “very interested in sitting down with Arntfield.”. Hargrove told me he hopes that eventually detectives will begin to use the algorithm to connect cases themselves, and that MAP will help solve a murder. Meanwhile, he is considering creating a companion site that tracks arson, and has begun compiling data on fires, though he hasn’t had time to post it yet. “There’s a link between serial arson and serial killings,” he said. “A lot of guys start out burning things.”We were walking in Alexandria by the river, along Hargrove’s usual route, and he said, “Our primary purpose is to gather as many records as possible.” He paused.

“It’s seductive how powerful these records are, though. Just through looking, you can spot serial killers. Maple 14 windows 32 bit.

In various places over various years, you can see that something god-awful has happened.” ♦.